|

This is the log created during my research residency at Beaconsfield Gallery in London. The final outcome was a new site-specific installation for 300 speakers, player piano and vacuum cleaner.

Although there will be lots about the pianola on this log, particularly at the beginning, the instrument is not meant to be central to the piece. The work is more about the acoustics of the gallery itself, with the piano used not so much as a musical instrument as a tool (along with 300 speakers) for exploring the acoustics of the space and as one element of an exploration of sculptural forms in relation to architectural space.

It is a 32-channel piece (think of stereo and multiply by 16 or Dolby 5.1 and multiply by 5.333): the movement of sound across the 32 channels and through the space was programmed using hardware and software developed primarily for use in large-scale theatre productions.

|

|

Lifting the pianola into the gallery. It weighs a great deal more than a normal piano because of the mechanical bits inside. When I was planning the project, I saw lots of pianolas on eBay for prices like £1.99 and regrettably based my budget on getting one for not much more. I even bid on one, but thankfully was outbid by someone who got it for £5.00. I'm sure that one and the majority of the eBay ones going for peanuts would require vast amounts of skill, labour and money to get working. I was very lucky to get this one (at the knock-down price of £320) because it had already been checked over by one of the world's foremost experts on pianolas, Rex Lawson, who just happened to know that the previous owner was looking to get rid of it within days of my contacting him through the website of the Pianola Institute. (Photo by Denise Hawrysio) |

|

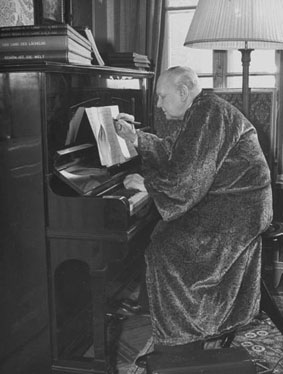

Pianola performer and scholar Rex Lawson in his studio with some of his 11,000 pianola rolls. I expected a pianola aficionado to be something of a character, but the beard took me aback somewhat. Rex has worked with Pierre Boulez and with Conlon Nancarrow, who is best known for his use of the player piano to experiment beyond the limits of the human performer.

Clip of Rex playing Conlon Nancarrow's Study No 7 and talking about working with the composer. Apologies for poor quality - it was shot on my phone. |

|

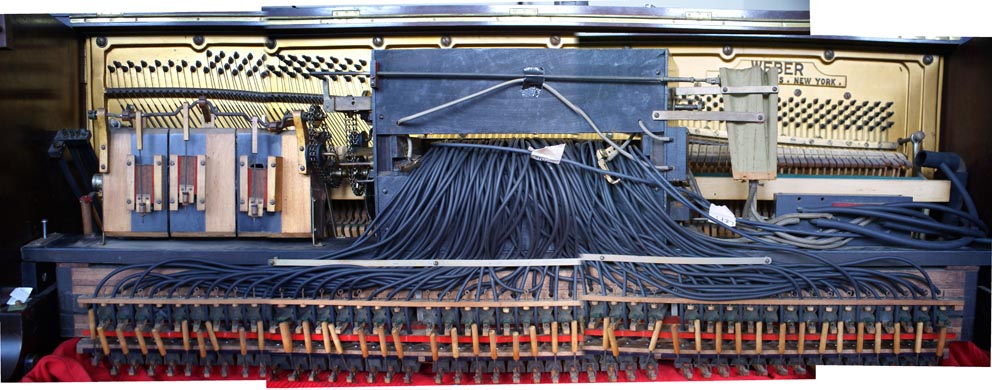

The correct term for my instrument is a Pianola Piano (or player piano) since it incorporates a player mechanism within an otherwise normal piano. Pianola is actually a trade name used by manufacturer Weber. Correctly speaking, a Pianola is a device that can be attached to the front of any piano, including a grand piano, as in this photo.

Note the rolls of blank paper in the background attached to Rex's perforating machine. |

|

Rex (with beard in 'working position') explaining the pianola mechanism to one of my two indispensible assistants, Antoine Bertin.

|

|

Each of the 88 notes on the piano is triggered by suction through rubber tubes. The tubes on this instrument were so old that they were as brittle as uncooked spaghetti, as Rex put it. Many of them were cracked, so many of the notes did not play, and the loss of pressure meant that the mechanism was very inefficient. As a consequence, you had to pedal like hell to get any sound at all.

|

|

Antoine and my other wonderful assistant, Kimmo Modig from Finland.

|

The 'stack' with its new tubes.

|

|

The things people throw away . |

|

Carrying out some acoustics tests. |

|

Analysis of the frequency response of the space to examine the way it 'colours' sound. |

|

Analysis of how long various frequencies reverberate in the space. |

|

Le déjeuner sur l'herbe in South London. Sometimes research can be gruelling. Here, we had to endure the vicious swinging tentacles of a willow tree and cream cakes as we engaged in fascinating conversation with Rex and his fellow members of the Pianola Institute, Bob (left), who is Andrew Lloyd Webber's piano tuner, and Dennis, who is a specialist in reproducing pianos. Reproducing pianos can be used to play back rolls 'recorded' by historical performers and composers such as Scriabin, Grieg and Fauré: in other words, when you hear the roll played you are hearing - on a real piano - an accurate reproduction of the original performance.

Many thanks are due to Rex, Bob and Dennis for their generous advice and support. |

|

Another trip to the civic amenities site, where I am now known as 'the speaker man'. One depot worker asked me "What are you making - a house?" There's an idea. Another worker surmised that the relatively few speakers being dumped at the moment is due to the recession. I have about 300 now, and still collecting. Wiring them all up should be fun. |

|

"In a very real sense, we are all aural architects. We function as aural architects when we select a seat at a restaurant, organise a living space, or position loudspeakers."

Blesser and Salter, Spaces Speak: Are you listening? |

|

Each speaker seems to have its own personality, projected through its design, the marks of use and abuse, and in some cases the modifications carried out by its owner(s) and even the smell. |

|

|

|

|

|

The blue dotted line on this roll is a guide for the player: the further to the right the is, the harder the player is meant to pedal, with the result that the dynamic intensity of the notes becomes greater. The speed of the music is not determined by how hard or fast you pedal but by a lever operated by the right hand, something that takes some getting used to. When I first sat at Rex's Pianola it felt a bit like trying to pat my head and rub my stomach at the same time or like riding a bicycle on which your speed has nothing to do with how fast you pedal. |

|

George Antheil's Ballet Mécanique was written for instruments including airplane propellors, electric bells and 16 player pianos:

In the late 1930s he finally settled in California where he became a successful movie composer. Aside from composing film scores, ballet, and neo-classical symphonies, he also put his astonishing talents to work designing a patent for torpedo guidance, assisted by the actress Hedy Lamarr (former wife of Fritz Mandl, arms dealer to the Nazis in the 30s). This torpedo system used punched paper rolls inspired by player piano technology to shift radio communications quickly and synchronously between a large number of bandwidths, thereby defeating enemy attempts to jam communications. This principle is now used in cellular telephone communications. (georgeantheil.com)

Still from Fernand Leger's film Ballet Mécanique, for which Antheil's piece was originally composed. |

|

We've been constructing and deconstructing and reconstructing speaker formations for weeks now. Some arrangements just seem to make themselves, and you don't know what they'll really look like until you've tried. Speaker Angel of the South? No. |

|

Probably not, but it has potential. File for later exploration. |

|

Ditto. |

|

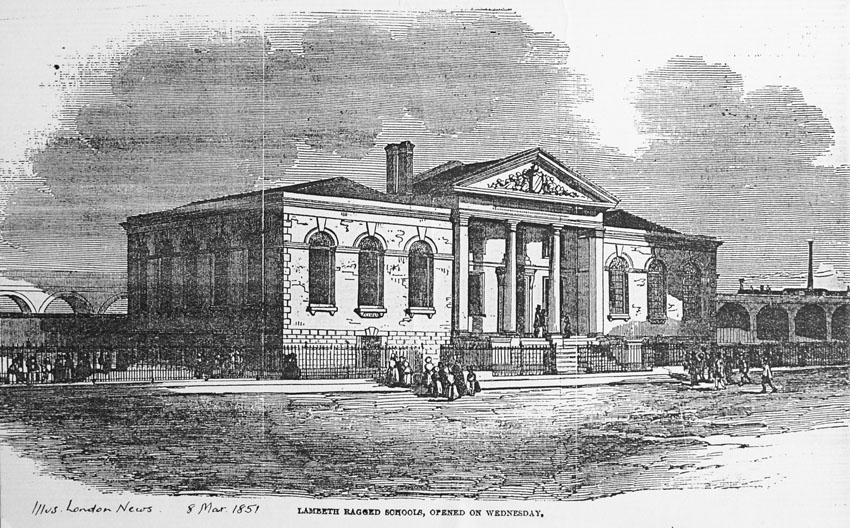

Nope. Again, I couldn't tell if it would 'work' until we'd done it. This is only 60-odd of my 300 speakers. The 18-foot high doorway originally joined the girls' wing of the Ragged School to the rest of the building, which was demolished to make way for expanding the railway line between Vauxhall and Waterloo. |

|

The piano player. This found vacuum cleaner will be used to power the player piano. Kimmo and I now know more about suction hose than we ever dreamed we'd know. |

|

Art Terry tuning the pianola; the player mechanism has been removed. I met Art years ago through Resonance FM, but I had no idea he tuned pianos - until I did a Google search for local piano tuners. Art is also a musician and has a recently revived programme on Resonance called Is Black Music. |

|

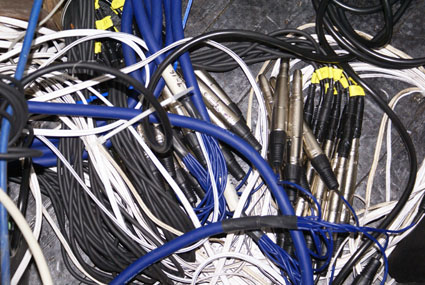

We've been wiring for 3 days. |

|

A home-made speaker bites the dust. |

Gallery One before my residency began. It's a wonderfully reverberant space: "Reverberation gives rise to an interactive experience, with the space entering into an acoustic dialogue with its occupants." (Blesser and Salter)

Gallery One before my residency began. It's a wonderfully reverberant space: "Reverberation gives rise to an interactive experience, with the space entering into an acoustic dialogue with its occupants." (Blesser and Salter) |

Athough smaller spaces still produce reverberation, as a listening visitor, you experience it as changing the tonal color of the direct sound, not as enveloping you. The acoustic dialogue between you and the space changes, but it remains a dialogue nevertheless. The spatial acoustics of a shower stall may induce you to sing because a small space has numerous discrete resonances. When the pitch and overtones of your voice coincide with these resonances, its loudness is greatly enhanced; when they shift away from the resonances, the intensity of your voices decreases dramatically. Rather than remaining neutral, the space reacts to the presence of some frequencies and not to others. Spaces may thus be said to have tonal preferences. A singer is an aural detective exploring the environment the way a child explores a toy. (Blesser and Salter, Spaces Speak: Are you listening?)

While I was reading the above this morning, there was a child in the school playground behind my flat who kept singing the same long note over and over and over. It was intensely irritating and distracting - that is, until it suddenly dawned on me that he was doing exactly what I was reading about at that very moment. The child had discovered that his voice became unnaturally loud at one specific pitch because of the way the surrounding architecture reinforced that frequency.

My developing work in the gallery is, in a sense, a dialogue with the physical and acoustic architecture of the space. Antoine and I will do some more tests once we've finished arranging the speakers to 'see' how the structure we've built affects the acoustics. The sculptural form of the piece has been determined in relation to both the physical and acoustic characteristics of the space; the sound of the installation will in turn be affected by the sculptural arrangement of the speakers as well as by the acoustics of the space andthe sounds that enter the space from beyond its walls.

|

|

The last of 300 speakers to be wired up. I'm deliberately not showing the final arrangement of the speakers and pianola on this website until after the installation opens on September 9. |

|

Rex 'helping' me re-cover the pneumatic that automates the piano's sustain pedal with fresh rubbercloth. This is the last bit of restoration on the Pianola I'm going to undertake for now. It's working well enough now for Rex to agree to play some Conlon Nancarrow studies for our event on Sept 24, which is a great honour. He'll also join myself and Ed Baxter in a conversation about pianolas, sound art and cultural redundancy. |

|

The 'tracker bar'. When perforations down the left side of the paper roll allow air to enter the large hole at the left end of the tracker bar, the pneumatic mechanism Rex is repairing in the above image pushes a lever which pulls the dampers off the piano strings so that all the strings resonate freely.

My Pianola was most likely manufactured in the 1920s by the Aeolian, Weber Piano and Pianola Company here in the UK, but the pianola technology dates back to the late 1890s. |

|

The unwanted speaker in its natural habitat. I realised the other day that I've never taken a photograph of any of the speakers I've found over the years in the place where they were actually found. I know this one looks like a setup, but it's not, I promise. |

|

Two of the workers at the Veolia recycling depot on what has to be one of my last visits. I have to draw the line somewhere, though I'm somewhat addicted to dropping in to see what sort of speakers have been abandoned since my last visit. |

|

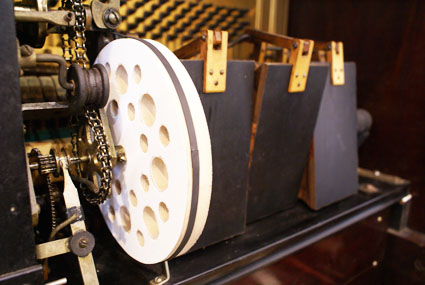

Getting into the nitty gritty. I have an idea for allowing me to reduce the minimum speed of the pianola roll by changing one of the sprockets in the drive mechnanism. So now I'm researching sprockets. The first thing I learned is that these are sprockets, not gears, because they're connected via a chain. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The vacuum cleaner/piano player needs to be moved outside. It's just too noisy within a piece that's meant to be subtle. Myself and curator David Crawforth wrestling with 45 metres of suction hose. Photo by Antoine Bertin. |

|

The hose en route to the vacuum cleaner's new home: the piece now extends beyond the gallery walls. Outside, nobody notices the addition of some white(ish) noise to the London soundscape.

Note the beautiful summer sky. This was mid-day. |

|

Now that the arrangement of the speakers has been finalised and all the wiring done, I'm finally free to work more on the sound and its spatial and temporal placement. In a sense, the speakers, the pianola and the space itself have become a single, complex 'metainstrument' with which to organise sounds in time and space. I want to make a piece that works with the ambient sounds of the space, but I have no interest in sampling the actual sounds - I'll be working in the space over the coming weeks, listening and creating synthetic sounds that work with the sounds that reach the space from beyond its walls: these synthetic sounds will be programmed to move through the 32-channels into which the 300 speakers have been organised.

|

|

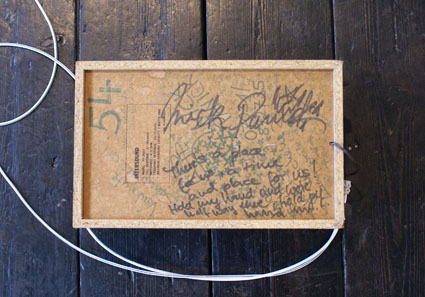

Canadian artists Ed Pien and Johannes Zits visited me in the gallery today along with Peter Freitag, an artist from Berlin. Johannes spotted the writing on the back of this little speaker. It was almost certainly at one time part of the sound system in a child or young teenager's bedroom. The words are from the song Somewhere in Westside Story. Johannes suggested "There's a place for us" might be an appropriate title for my installation, which is still untitled.

Nice idea. Come to think of it, that song contains a lot of possible titles...

a) There's a place for us

or

b) A time and a place for us

or

c) A time and a place

or

d) We'll find a new way of living

or

e) A new way of living

or

f)

Somehow, someday, somewhere

|

|

One of these cables or connectors is not working... |

|

Inspiration from the recycling depot. Oddly enough, the high round window is in a the same position as the little round window at Beaconsfield. Both are Victorian buildings. This building once housed a swimming pool which was part of the Public Baths servicing the Victorian blocks of flats in which I now live. There were in fact 3 swimming pools in this large complex, as well as baths for washing, since there were no bathrooms in the flats as they were originally planned. It was built in the late 1880s; Beaconsfield in 1851. The Public Baths are now occupied by the recycling depot and a Buddhist centre. |

|

An earlier, rejected arrangement using about half the speakers. My assistants, Kimmo and Antoine, and I all enjoyed working physically with sculptural materials for a change instead of sitting in front of a computer, which is what we all seem to do most of the time these days. We built formations which then gave us ideas for other arrangements and the final arrangement could only have been arrived at through this iterative process of experimentation. The arrangements were assessed not only on their visual impact but on the possibilities for interesting and complex diffusion of sound. Although this arrangement is interesting visually and worked well in the space, it wasn't the most suited to exploring spatial acoustics. In a highly reverberant space like this, such an arrangement would result in most sounds apparently coming from pretty much the same place, even with 32 separate channels. That, too could be interesting, and like many of the arrangements we tried this one was hard to reject and could easily be the basis for another piece, another time.

|

|

Through the round window, you can see trains passing on the busy elevated line between Vauxhall and Waterloo. The sound of the trains is surprisingly complex and beautiful and, because of the speed and freqeuncy at which they pass by, creates a gentle rhythm which is having a definite influence on the atmosphere of the installation. At the moment, I'm creating synthetic sounds in response to these and other sounds from outside as they are, in effect, filtered by the building itself before reaching the gallery.

The gallery is in the very centre of this image. A train can be seen approaching from the bottom left. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The tempo governor. I still can't get the pianola playing as slowly as I'd like, so I've taken this out and hope Rex can help me find out why the mechanism is not behaving as it should at very slow tempos. Granted, I'm trying to get the pianola going more slowly than it was really designed to go, but there's no reason it shouldn't be capable of what I'm trying to achieve. I hope. |

|

Unrelated to the project except that I saw this while cycling home from the gallery. Near the Elephant and Castle. |

|

To my frustration, neither the smaller aluminium sprocket so expertly made for me by Tom Taylor nor the servicing of the tempo governor by Rex have solved the problem I've been having with getting the pianola to play as slowly as I'd like. So I threw one last day at the problem and lo and behold my crudely made mdf wheel and rubber band does the trick. Thanks, Tom, for the suggestion! Needs some refinement, but at last I'm moving again. |

|

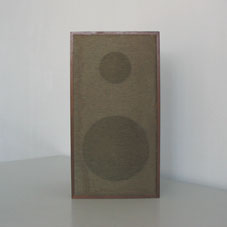

Hard to believe anybody still has this model of speaker - I found my first one like this on the street more than 20 years ago, and it, like this one, is now part of the installation. |

|

|

|

Jeff Koons. |

|

A real Koons in South London. |

Note the train approaching from the right. It was expansion of this train line that led to the destruction of the right two thirds of the building. |

|

Later version of the new drive wheel. The holes are just to make it a bit lighter. |

|

I ran into a friend, artist Paul Noble, the other night, and he told me about a book called Agapé Agape by American writer William Gaddis. Written in 1998 while Gaddis was dying of prostate cancer and under the influence of strong drugs, the book is a stream of consciousness rant with the player piano and its ‘tiny felt-tipped wooden fingers’ at its heart. As Sven Birkerts writes, ‘The player piano was for Gaddis a significantly symbolic development and its history illuminated a great deal about the growth of binary thinking and what he saw as the ephochal shift from artistic to entertainment values.’

Because that’s where it all came from, where the technology came from right down to that paper roll with the holes in it where the computer came from, you see? Just take a minute to explain all this computer madness besotted by science besotted by technology by this explosion of progress and the information revolution what we’re really besotted by is people making millions, making billions from computer chips computer circuitry computer programs one man making thirty billion dollars in a year because that’s what we’ve always been besotted by … what America’s all about, what it’s always been about that thirty billion dollars? What the computer’s all about what all of it’s all about, movie stars, ball players, what science is all about, try to pin it on some humble genius so Pascal shows up age nineteen with his digital adding machine, Leibniz with one that multiplies and divides and finally Babbage and his Difference Engine, Babbage and his Analytical Engine with its punched cards Babbage the grandfather of the modern computer so it’s Babbage Babbage Babbage but he got his idea from Jacquard’s loom so that’s all you ever hear, Jacquard’s loom Jacquard’s loom Jacquard’s loom hits you square in the belly …. The piano was the epidemic, it was the plague spreading across America a hundred years ago with its punched paper roll at the heart of the whole thing, of the frenzy of invention and mechanization and democracy and how to have art without the artist and automation, cybernetics you can see where the, damn!

|

|

Franz Lehár (1870-1948), composer of the operetta Zigeunerliebe (Gypsy Love) in 1909. The piano roll transcription of some parts of the operetta is the material I'm using in this piece. But as mentioned above, I have altered the tracker bar so that it only plays some of the notes.

My use of this musical material is just one of many chance elements involved in the piece: Gypsy Love happened to be one of the rolls Rex was kind enough to give me when I began the project. It is the longest of the rolls, and I needed something that would last at least a day when slowed down so that it wouldn't need rewinding. It was also rather fun to play when we were restoring the Pianola.

My friend and colleague Dr John McAllister wrote to me today... "Hitler always claimed Wagner was his favourite composer, but I read once that secretly he found Wagner's operas rather bum-numbing and preferred Lehár." Hitler awarded Lehár the Goethe-Medaille für Kunst und Wissenschaft in 1940.

Despite having a Jewish wife, Lehár remained in Vienna throughout the war. His friend and occasional librettist Fritz Lohner died at Auschwitz. |

|

Sound-wise, this is the most indeterminate piece I've ever made. There are essentially 3 elements to the sound, and they constantly shift in relation to each other, temporally, resulting in a balance of order and disorder which is reflected in the physical arrangement of the speakers.

The three elements are a) the computer arrangement of sounds that I have synthesised or recorded within the space, b) the pianola part and c) the ambient sounds of the space which act as a continuous additional soundtrack. The last of these is interesting because the gallery is nestled next to a very busy train line, and it's on a curve so the wheels grind and make a fantastic sound. There's also fairly quiet but regular traffic on the road in front of the gallery, and the sound of cars and motorbikes and lorries has also become part of the texture and rhythm of the piece. The envelope and tempo of each programmed sound is designed to mirror those coming in from outside. The area is zoned for light industry, so there are sounds of a saw and other industrial sounds that can be heard at irregular intervals. It has been interesting making a 32-channel sound piece which is totally dependent on this continuous extra track which I can neither influence nor turn off.

The pianola stops and starts at irregular intervals according to my programming; I've masked off many of the holes on the 'tracker bar' and I have finally made the ‘wind motor’ turn the paper roll very, very slowly. The composed element allows me to exercise my control freakery, but I can never tell exactly what the environment or the pianola will do at any given moment. Sometimes the pianola part is quite busy, at other times it will only play one or two notes in several minutes. The piece will never repeat because the programmed sound, the piano notes and the environmental sounds will never be in the same place twice.

|

|

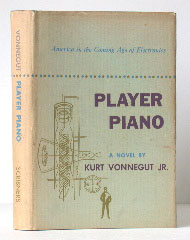

I'm slightly surprised at the small part played by the player piano in this Vonnegut novel, considering the title, but it's a great read nonetheless. Written in 1952, it's set in a dystopic future in which humans are being increasingly replaced by machines. As in Gaddis' Agapé Agape, the player piano is used as a symbol of the mechanisation of both labour and culture. In Vonnegut's town of Ilium, almost everyone is either a manager or engineer with a PhD or else a member of the lumpen proletariat living on the other side of the river. Before I got my own PhD I used refer to the proliferation of doctorates these days as PhDitis. Now I just refer to the fact that I used to refer to the proliferation of....

In this passage, Mr Haycox is an old guy taking care of a traditional farm nobody wants to buy from Dr Pond, the real estate agent, because most farming has been automated for years:

"Call yourself a doctor, too, do you?" said Mr. Haycox.

"I think I can say without fear of contradiction that I earned that degree," said Doctor Pond cooly. "My thesis was the third longest in any field in the country that year--eight hundred and ninety-six pages, double-spaced, with narrow margins."

"Real-estate salesman," said Mr. Haycox. He looked back and forth between Paul and Doctor Pond, waiting for them to say something worth his attention. When they'd failed to rally after twenty seconds, he turned to go. "I'm doctor of cowshit, pigshit, and chickenshit," he said. "When you doctors figure out what you want, you'll find me out in the barn shoveling my thesis."

|

|

Installation for 300 speakers, Pianola and vacuum cleaner

Beaconsfield Gallery 1, London, 2009

(Photo by Steve Ibb)

|

"Monumental minimalism" (Marcia Farquhar)

"Miminal monumentalism" (Jem Finer)

Click above to hear my interview with William English on ResonanceFM's Wavelength

Click above for my interview with Zoe Martlew on BBC Radio 3's Hear and Now

Click above to read Clive Bell's article in the Wire magazine

|

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

|